With this knife it’s tough for me to do that thing I do where I bury the lede in order to keep suspense for the first couple of paragraphs in order hook the reader before I reveal whatever its quirk is.

This is the WE Knife Double Helix, and it’s easy to see what its deal is right away because it wears its underpants on the outside.

At its core the Double Helix is, more or less, an Axis lock style crossbar locking folder. However, rather than the typical pair of hair-thin “Omega” springs hidden inside the handles…

…Instead there’s this trebble-clef external spring that runs almost the entire length of the knife. There are two, actually, with an identical but mirrored one on the other side. That’s certainly a novel way to do it, and for this it was awarded “Most Innovative New Knife 2018” by Knife News. I’m sure WE will be trumpeting that at anyone who’ll listen – and anyone who won’t – until the sun burns out.

In my prior ramblings, I’m certain I’ve told you many times how the Axis lock is my favorite mechanism out of all the various non-balisong folders. You’re probably sick of hearing it, along with the note that Benchmade’s patent on it expired in 2018, enabling many other knifemakers to have a crack at the idea.

Part of why I like the Axis lock is its inherent capability, when properly designed and implemented anyway, to do the “Axis flick.” That is, you can hold the crossbar back and just flick the knife open without any other manual intervention. The jury’s out on whether or not this is actually an originally intended function of the mechanism.

Well, for its part the Double Helix doesn’t leave much ambiguity about how its designers intended it to be opened. As you can see it is completely lacking in any kind of thumb stud, disk, hole, hook, or any other apparatus to aid you in getting it open with your thumb. And to further compound matters, unlike normal Axis lock folders its lock also resolutely holds the blade shut. You absolutely cannot open it without pulling the crossbar back.

The Double Helix is a fancy knife with ball bearing pivots, so with all of the above taken together we can only conclude that it’s meant to be Axis-flicked open with a snap of the wrist. The only other way to do it is to use two hands, and what kind of self respecting individual is going to do that?

The flies in the ointment with the action are twofold, though. First is that the Double Helix is not one iota longer than it needs to be, which means that the tip of its 3-1/4" drop pointed blade passes extremely closely to the tail end of the knife. It’s therefore not only possible but downright likely that some of the meat from the heel of your hand will at some point get squished into the gap between the handle halves and then the point will graze you as it goes by.

Second is that, visually striking though they may be, those two external springs are actually rather stout and it takes quite a bit of force to disengage the lock.

There is a pocket clip, which stands on long standoffs to ensure it clears the spring and is also for no particular reason not reversible. As usual there’s no mechanical impetus as to why it couldn’t be; there just aren’t any holes for it on the other side even though both handle halves are total mirror images of each other. Apparently because WE decided they just couldn’t be bothered. It’s just as well, probably, because screws holding the end of the spring down have cylindrical heads that sit proud of the face of the spring by several millimeters and are incredibly snaggy. They wind up between the clip and your pants fabric, making the Double Helix nearly impossible to draw in a hurry without either tearing your pants fabric off or giving yourself an atomic wedgie. Both the clip and its standoffs are easily removable, although there is no lanyard hole either so if you do that you’ll just have to leave the thing bouncing around your laptop bag like some kind of heathen, or something.

There is some thickness to the springs, and also to the handles – arguably probably more than there needs to be just to get the mechanism to work – which makes the Double Helix pretty chonkers. This is completely notwithstanding the fact that its groovy pivot screw with the machined-in “WE” logo is flush fitting.

It’s 0.648" thick just across the handle slabs not including any of the other greebles; including the thickness of the two crossbar lock heads it’s a whopping 0.770" and including the clip it’s an even more ridiculous 0.807". And of course being made of zooty premium materials like titanium and aluminum, it’s not as hefty as you’d expect: 99.8 grams or 3.52 ounces. Closed it’s precisely 4-1/2" long, and open it’s 7-13/16".

The blade is S35VN, surely mostly in order to maintain credibility among its intended purchasing demographic, and is 0.133" thick. It’s fullered, and has a nicely rounded spine that’s easily the least snaggy part of the entire knife. Reviewers who are more qualified than me have spent many words on its hollow grind and its excellent general purpose cutting ability, but I won’t because this is a collector’s knife and to the first couple of decimal places nobody is going to cut anything demanding with it anyway.

According to the stipulations of a very particular gypsy curse, I am incapable of giving an overview of any knife with a weird mechanism without taking it apart to see how it works. Although in the case of the Double Helix, pretty much everything interesting is visible from the outside.

I took it apart anyway.

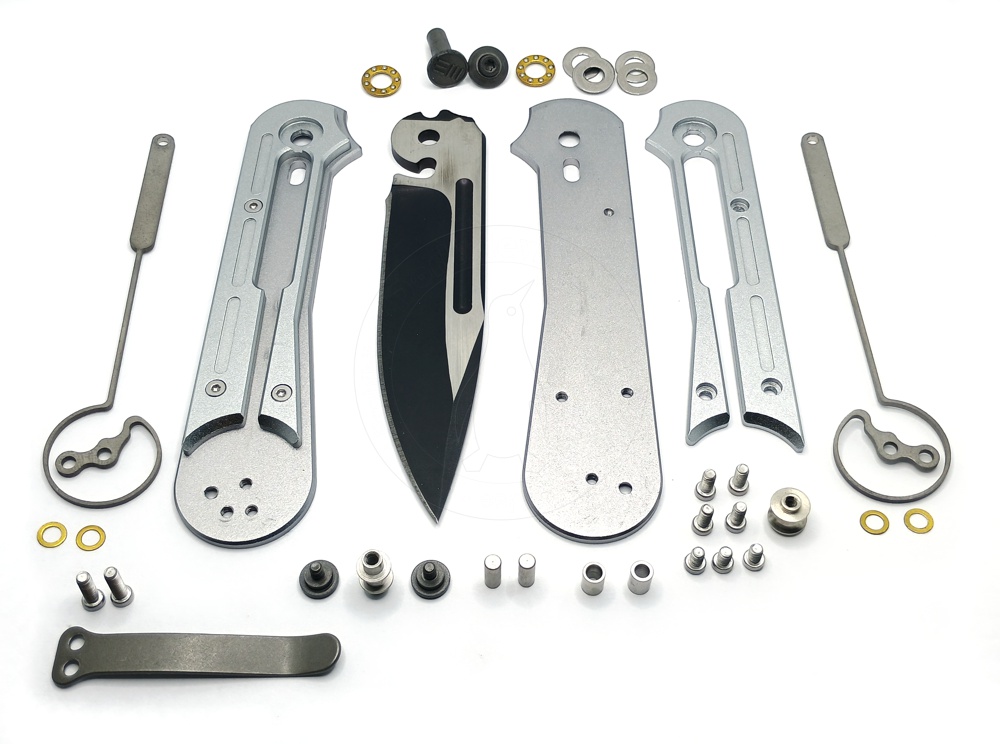

Being firmly in the enthusiast knife category, the Double Helix was not at all difficult to take apart. It’s all T8 and T6 Torx screws, as you’d expect. And also as an enthusiast knife, it breaks apart into a ridiculous number of individual parts, apparently to vainly attempt to justify its price tag.

This is most of the hardware. Each handle slab is actually two pieces, which is completely unnecessary from both a production and mechanical standpoint, but that’s how it is anyway. I only took one of them apart for my disassembly photo, so the lineup above is short three additional screws. The trim collar around the male side of the pivot screw is also a separate piece, and it has two end stop pins. And also three washers per side of the pivot, for some reason. That all adds up to no less than 35 individual pieces of hardware required to assemble this, not including the blade itself, both pieces of both handle halves, the clip, and the springs.

Because the crossbar has to pass through holes in the ends of the springs externally, it is somewhat unusually a multi-piece design. It’s right in the middle of the photo above, and it consists of a flanged center barrel while the nubbins on the outside that you interact with can be unscrewed. This is necessary because the usual method of installing an Axis crossbar through an offset pair of channels hidden under the handle scales obviously would not work in this case.

Note also the alarmingly tiny little spacer washers that go between the handle slabs and the springs, which are bound to disappear forever if you drop one on the carpet. So watch it.

Here you can see WE’s weirdo crossbar lock track, including the dog-leg that locks it in place in the closed position. The general consensus online seems to be that this is supposed to be for “safe” pocket carry, as opposed to a weird design oversight, which I find highly dubious given that A) nobody in all of recorded history has ever had a problem with an Axis knife falling open in their pocket, and B) nobody is going to pocket carry this more than once anyway, see also the situation with the clip, above.

The Inevitable Conclusion

This is one of those things built purely for knife collectors, and normal people probably need not apply. Knife mechanisms are sort of like the quantum multiverse theory – for any given possible way to do it, it is not only likely but downright inevitable that someone will eventually try.

I like the Double Helix’s core conceit. It’s just all the details surrounding its execution that I take exception to.

In my opinion it would not take much of a redesign to allow the Double Helix to retain its groovy external spring, but also make it significantly less irritating to carry and use. Just not locking the blade shut would put us well on our way, in addition to sinking the spring into the handle a bit and giving all the mounting screws countersunk heads.

WE, if you need to take me on board as a design consultant to straighten all this out I’ll happily do so, and you’ll find my rates to be very reasonable.

I think that’s entirely up to interpretation, and you can rotate the screw in place so it’ll appear right side up either with the knife open and edge downwards, or closed with the spine downwards. I went with the former.