- cross-posted to:

- hackernews@derp.foo

- technews@radiation.party

- linux@lemmy.ml

- cross-posted to:

- hackernews@derp.foo

- technews@radiation.party

- linux@lemmy.ml

That is a long posting, and TBH I did not read it all. I take issue with most of the arguments, that are brought up, because I think they are a bit in bad faith or deliberately ignoring some counterarguments.

Core library developers are finally seeing the benefits of maintaining compatibility.

This might be true, but true is also that just recently a change in Glibc broke a some games on Steam.

Despite this, many developers are not interested in depending on a stable base of libraries for binary software.

Why has the author such a contemptuous tone? As if developers would like to bloat the system out of spite. Unstable ABIs is still a problem, as I linked. Flatpak is a solution to most of those stability problems.

There are a lot more weak arguments in this article.

Sharing runtimes is a bit similar to existing package managers. If I install KCalc under Gnome, it pulls also a lot of dependencies under classical package managers. Sure, it is worse under Flatpak, but kind of similar. If storage is too much of a problem, then package maintainer will use only a few different runtimes. Otherwise, Flatpak will just not be usable.

Sandboxing is not perfect, but we have to start somewhere. Android fox example has a very sophisticated sandboxing and package mangers like Flatpak can get there too. Yes, it still has its problems, but they are solvable.

All in all, most problems with Flatpak are problems, that can be solved. I really dislike the tone of the author. Flatpaks are not from the devil, they are here to solve problems. I am interested in a constructive discussion, not this.

All in all, most problems with Flatpak are problems, that can be solved

No, flatpak and similar things are designed to bypass the relation of trust between end users and Linux distributions. Users are required to either blindly rely the upstream authors with the sandboxing, privacy, legal compliance and general quality or do extensive vetting and configuration by themselves.

Additionally the approach of throwing every dependency in one big blob removes the ability to receive fast, targeted security updates for critical libraries (e.g. OpenSSL). And there is no practical way to receive notifications for vulnerabilities and to act on them for the average user.

Traditional Linux distributions carefully backport security fixes to previous releases, allowing users to fix vulnerabilities without being force to upgrade their software to newer releases. New releases might contain unwanted features or be too heavy for older hardware, or break backward compatibility.

With Flatpak, even if the upstream developer forever releases new packages every time a vulnerability is found in the entire blob, end users are forced to choose between keeping the vulnerable version or update it. Plus, the authors might simply abandon the project.

Furthermore, Flatpak, Snap etc and similarly Docker do not require 3rd party / peer review of the software. Given the size of the blobs it would very impractical to review their contents even if it was required.

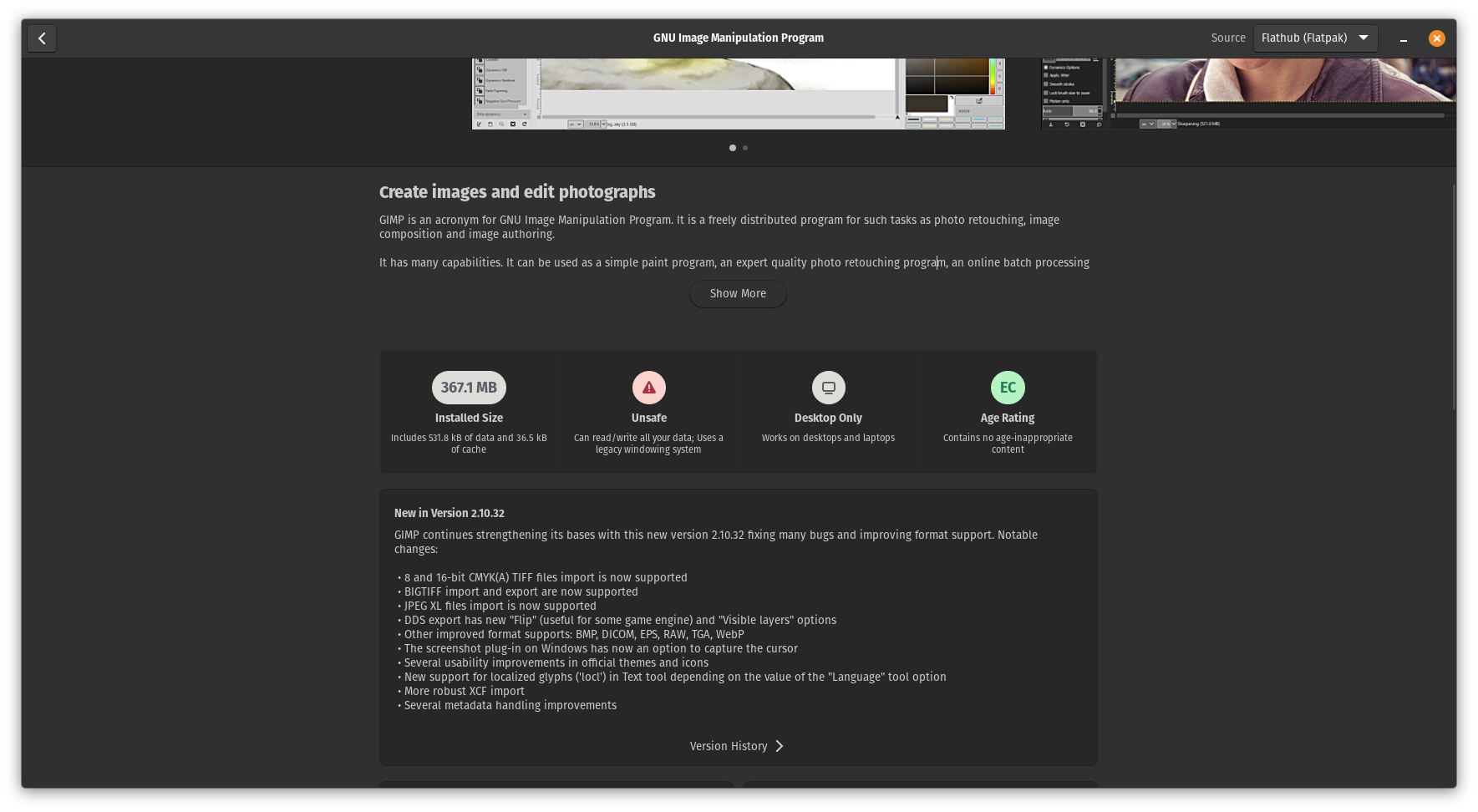

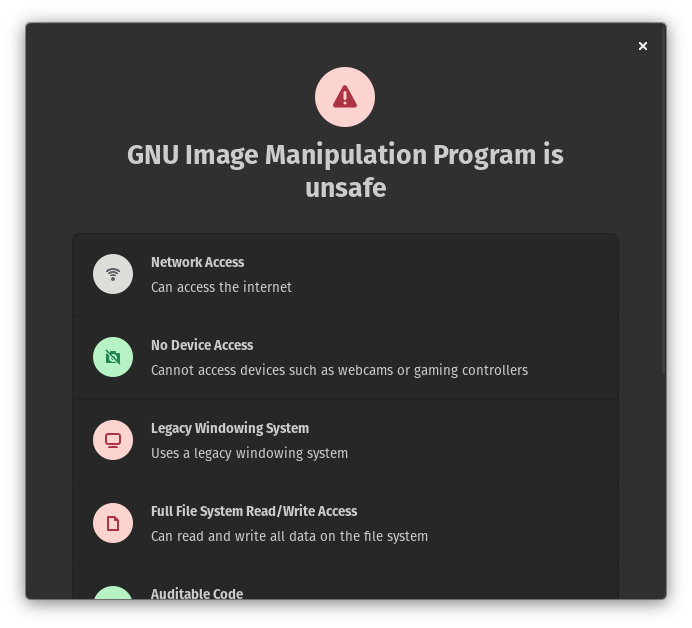

Fedora claims GIMP is sandboxed. If you click “High” next to “Permissions”, you see a little exclamation mark saying it has “File system” permissions.

it’s a Fedora problem, not a Flatpak problem (this is GNOME Software on Pop OS 22.04)

seriously though, i found the essay…wanting. it was far too focused on the problems, which is of course fine if you don’t have solutions to them, but the author does have solutions (presented at the very end). the tone is excessively pessimistic, which would turn a lot of readers off from reading these legitimate grievances

This is a Flatpak problem. Its design requires the user to either trust the upstream developers to set the sandboxing properly or learn how to do it and spend time configuring each and every application as needed. This is not practical.

In traditional Linux distributions there is a trusted package mantainer that reviews software and configurations with the user’s needs in mind.

or learn how to do it and spend time configuring each and every application as needed

And even if they were to spend the time, afaik there’s simply no right way to configure a flatpak like GIMP so it can edit any file from any arbitrary location they might want without first giving it read/write permissions for every single of those locations and allowing the program to access those whole folder trees at any point in time without the user knowing (making it “unsafe”).

It shouldn’t have to be this way, there could be a Flatpak API for requesting the user for a file to open with their explicit consent, without requiring constant micro-management of the flatpak settings nor pushing the user to give it free access to entire folders. The issue is that Flatpak tries to be transparent to the app devs so such level of integration is unlikely to happen with its current philosophy.

there could be a Flatpak API for requesting the user for a file to open with their explicit consent

That would not be Flatkpak then. It would be an OS component, much like Android has a file opener implemented as an independent process IIRC.

That’s a very loose definition of “OS Component”. At that point you might as well consider the web browser an “OS Component” too, or frameworks like Retroarch, who offer a filesystem API for their libretro cores.

But even if we accepted that loose definition, so what? even as it is today Flatpak is already an “OS Component” integrated already in many distros (it’s even a freedesktop.org standard), and it already implements a filesystem interface layer for its apps. As I said, I think the real reason they won’t do it is because they keep wanting to be transparent to the app devs (ie. they don’t want them to have to support Flatpak-specific APIs). Which is why I think there needs to be a change of philosophy if they want app containerization to be seamless, safe and generally useful.

You are missing the point. A process-independent file opener that is used by all applications to access files provides user-friendly security. This would be a core component of an OS so the description is correct.

You are missing the point. A process-independent file opener that is used by all applications to access files provides user-friendly security.

But that was essentially what I said… I’m the one who proposed something like that 2 comments ago.

This would be a core component of an OS so the description is correct.

Again, I disagree that “this would be a core component of an OS”. You did not address any of my points, so I don’t see how it follows that “the description is correct”. The term “core OS component” is subjective to begin with.

But even if you wanted to label it that way, it wouldn’t make any difference. That’s just a label you are putting on it, it would not make Flatpak any less of an app distribution / management system with focus on cross-distro compatibility and containerization. Flatpak would still be Flatpak. Whether or not you want to consider it a core part of the OS is not important.

And Flatpak already uses independent processes to manage the whole container & runtime that the app uses for access to the system resources, which already closely matches what you defined as “a core component of an OS”.

The author is right and I hate it

See also: Flatpak - a security nightmare

I have mixed feelings about Flatpak. On one hand it solves a very practical problem in Linux (packaging software once for all distros). On the other hand it has huge implementation problems as mentioned in this article. I also don’t like centralizing software in one place.

You can install different flatpak repos without really having to depend on one specific central repository, so I’d say the “centralizing software” issue is not that different from any typical package manager.

That said, I do agree that Flatpak has a lot of issues. Specifically the problems with redundancy and security. Personally I find Guix/Nix offers better solutions to many of the problems Flatpak tries to fix.

This is much more akin to how iOS and Android work. But it means abandoning like 95% of Flatpak. It would be such a drastic change that they might as well start over under a different name. I don’t see it happening.

😴😴😴😴

In future posts I’ll be going over some of the problems with targeting desktop Linux directly, presenting some of the stuff I’m working on, and hopefully coming up with real solutions that don’t depend on alternate runtimes.

at least

It’s interesting to compare these package managers to service containerization, I.e docker, podman etc. There it works pretty well, but many of these benefits don’t seem to be present in desktop use.

These “package managers” (in quotes, as I find them a bad substitute for an actual package manager, but that’s a sidenote) effectively use the same underlying technology,

cgroupsetc. asdockercontainers etc.The thing is, what makes sense on the server, doesn’t necessarily make sense on the desktop. It makes sense to prioritize developer comfort over disk space use in server context, for example; it makes way less sense to do so in the desktop context.

Yeah, for example, it’s nice not having to manually fiddle with PHP dependencies etc. when it comes to web servers, but desktop apps are rarely like this. They just have their executable, and seldom require any serious configuration.

Desktop apps can have a crap-ton of dependencies and a finicky requirements around specific versions. That’s one of the reasons why “flatsnappimage” stuff got created in the first place — to go around the limitations of Linux distribution package manager dependency management model.

And we do need a better way to deal with this. But the “flatsnappimage” approach is not that, IMVHO, as it’s clearly driven by other considerations (like the “we want to have an app store we control” thing mentioned in the article).

But the thing is, in a server context you have developers, sysadmins, and that’s kinda it. They can make informed decisions on how to manage stuff, and making it easier for the developers to deploy stuff is a reasonably good strategy.

On the desktop you have app developers, OS maintainers, and users. Users often will not be able to make anywhere near as informed decisions as developers and maintainers. Focusing on developer comfort basically leads to ignoring users’ needs (like: “a calculator app should not need a 2.8GiB of stuff just for itself”).