spoiler

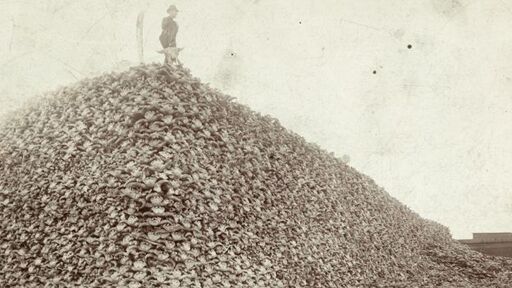

The photo of two men standing on a mountain of bison skulls is well known as a symbol of hunting during the colonisation of the US. But there’s a more sinister story behind it – with a surprising modern message.

Two men in black suits and bowler hats pose with a gravity-defying mound of bison skulls. The 19th-Century image is disturbing – thousands upon thousands of skulls piled in neat rows, towering towards the sky. But beneath the macabre first impression, the photo holds a darker secret still. These skulls aren’t just the product of overzealous hunting in the US – and those men aren’t hunters, either.

The skulls, experts say, are the evidence of an organised, carefully calculated campaign to eradicate the bison, deprive Native Americans of a vital resource, and drive the few communities that survived onto small reservations where they could be controlled by the newly arrived white settlers.

“This image is an example of colonial celebration of destruction,” says Tasha Hubbard, a Cree filmmaker who is an associate professor at the Faculty of Native Studies at the University of Alberta in Canada. Hubbard describes the extermination of the bison as a “strategic” part of colonial expansion. The eradication of the animal “was seen as the taming of the West, of domesticating this wild space that was needed in order for expansion of settlement”.

The colonial mass slaughter of bison dealt a lasting blow to tribes that relied on the animal for sustenance. In the aftermath, nations reliant on bison fared measurably, permanently worse than nations that were never bison-reliant, for example suffering from higher child mortality than those other nations, according to a comparative study. The study concludes that the loss set the bison nations on a fundamentally different trajectory that continues to this day.

Native Americans had hunted bison for centuries. For bison nations, it was part of their primarily nomadic culture and the animals provided them with vital sustenance – meat for food, hides for shelter and clothing, and bones for tools. (In common parlance and historical sources, the animals are often referred to as buffalo, as that’s what early settlers called them – though the two are in fact different.)

Indigenous peoples across North America relied on the animal, Hubbard says. “So to remove that keystone species was to weaponise starvation against indigenous peoples: to weaken us in order to control us and remove us from our territories.”

Despite the bisons’ usefulness, estimates put the Native American hunters’ take at less than 100,000 a year, hardly making a dent on the early 1800s population of between 30 and 60 million bison.

By 1 January 1889, there were just 456 pure-breed bison left in the US – and 256 of them were in captivity, protected in Yellowstone National Park and a handful of other sanctuaries.

The reasons for the mass bison slaughter are numerous: they include the building of three railway lines through the most populous bison areas, which brought new demand for the animal’s hide and meat; modern rifles that made killing bison relatively easy; a lack of protective measures which could have curbed hunting. But there was also more sinister, targeted reason for the animals’ decline than just an increased demand for bison products – more on this later. And even the settlers’ seemingly practical need for bison meat and hide was ultimately intertwined with colonisation and conquest, historians say.

“A desire for wealth and power in the form of land ownership, chattel slavery, the drive for unending growth and profit, and the commodification of natural resources is the reason for the intense overhunting of bison and the political and physical attacks on indigenous nationhood and humanity over five centuries,” says Bethany Hughes, a member of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, and assistant professor at the University of Michigan’s department of Native American studies.

When the Transcontinental Railroad was completed in 1869, it accelerated the decimation of the species. In 1871, a Pennsylvania tannery developed a method of converting bison hides into commercial leather. Swarms of hide hunters decimated central plains herds with a “shocking rapidity”, one study noted.

The infamous image of bison skulls was taken at the Michigan Carbon Works, a refinery that processed bones. There, the bison bones were processed into charcoal that the sugar industry used to filter and purify sugar – the bones were also used as glue and fertiliser.

“This photo records a remarkably successful business that was built on the waste created by American Western expansion and its accompanying racial logics of Native American inferiority,” says Hughes.

“Colonialism and capitalism travel together,” Hughes adds. "To benefit from and encourage the kind of economic success this company had processing bison bones, [which] were the byproduct of the sometimes-violent tactics of American settler colonial expansion, was to benefit from – and participate in – colonial projects that stripped Indigenous peoples of land, nationhood, and culture.

“This photo is not a bracing reminder of the harms of colonial pasts. It is an indictment on commercial consumption practices that obscure the material and ethical conditions that make luxuries like refined sugar readily available and seemingly benign.”

Killing bison was also part of military campaigns that used resource deprivation as a tactical move.

It has been well documented that Western army officials sent soldiers to kill bison as a way of depleting Native American resources during the colonisation of the US. An analysis by historian Robert Wooster in his book The Military and United States Indian Policy acknowledges that General Phillip Sheridan, an army officer responsible for the “Total War” strategy against Southern Plains tribes,“recognised that eliminating the buffalo might be the best way to force Indians to change their nomadic habits”.

Sheridan was recorded telling legislators who were trying to pass laws to protect the dwindling herds: “[Hunters] are destroying the Indians’ commissary. And it is a well known fact that an army losing its base of supplies is placed at a great disadvantage…for a lasting peace, let them kill, skin and sell until the buffaloes are exterminated.”

Sheridan wrote in a letter to a fellow general in 1868: “The best way for the government is to now make [the tribes] poor by the destruction of their stock, and then settle them on the lands allotted to them.”

Another army official – Lieutenant Colonel Dodge – told a hunter: “Kill every buffalo you can! Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone.”

The Native American tribes knew what was happening. Satanta, chief of the Kiowas tribe, in the Great Plains,recognised that “to destroy the buffalo meant the destruction of the Indian” – as Billy Dixon, a bison hunter and frontiersman from Texas, recalled in his autobiography. “General Phil. Sheridan, to subdue and conquer the Plains tribes for all time, urged and practiced the very thing that Satanta was fearful might happen,” Dixon added.

Depriving the Native Americans of their bison meant they were forced to move onto the new reservations the Western army had established for them, in order to grow food to survive.

The army’s tactics worked. The Kiowa Tribe members were later driven onto a reservation in Oklahoma. Within one generation, the average height of Native Americans who had relied heavily on bison and so were most impacted by the slaughter dropped by more than an inch (2.5cm). By the early 20th Century, child mortality was 16% higher, and the income per capita among bison nations has remains 25% lower compared to nations that weren’t so reliant on bison.

However there has been some debate over the years over the kill-off. How could hunters kill 30 to 60 million animals? That was the question posed by a 2018 study which offered a disease epidemic as the answer. Two diseases in the country at the time – anthrax in Nebraska and Texas tick fever in Montana – would have been “sufficiently deadly to wipe out tens of millions of animals”, the study notes.

Regardless of the cause, the bison populations never fully recovered and the species is still listed as near-threatened. But in recent years efforts have been made to bring bison back to the Great Plains (they are incredibly important to the prairies ecosystem). In the US government’s 2023 Inflation Reduction Act, $25m (£19.7m) was pledged to restore bison across the US.

Smaller efforts are already underway: 1,000 bison raised on reserves belonging to environmental non-profit The Nature Conservancy have been returned to their ancestral grazing lands. A restoration project in Montana aims to bring 5,000 bison back to the prairies and tribes have returned 250 bison to their land in a partnership with the National Wildlife Federation.

The message behind the striking mount of bison skulls image has been lost over time, adds Hughes, who says the image carries a simplistic message that allows viewers to feel sadness about the past, but does not force them to confront “the ways that colonial and capitalist systems continue to negatively shape our environment and our lives”.

"More than that, this photo points to the ways that consumers of products are the engine that drives the colonial machine.

“If you dehumanise another person or objectify a living being as a ‘natural resource’ you have revealed your own lack of humanity and a misunderstanding of what it means to live in relationship with the world around you,” Hughes says. “This is an important message to share with the public because this is an ongoing problem, not a historical one.”

The irony of ending the piece this way seems lost on the author.